I started this April 30, 2009

Here I lay, on the floor, with pen and paper, and an earnest prayer on my lips; “I want to write, Dear God, show me what to write.”

Introduction

Loneliness, for me, is the truest form of torture; a realization that I came to a number of years ago. Jogging gives you time to think, and being alone gives you more time. I’m a thinker; not about the little, shallow things of life. I’m not interested in the surface; from my earliest memories I’ve always been preoccupied with the why’s of life. As I went on my morning jog, I wondered why I am so tormented by feeling so alone. Well, I am alone, most of the time, but some people are comfortable with that, I am not. I am very uncomfortable with being alone; I feel the silence of alone. There is no companionship, no greeting, no friendship. No, I am not my friend, and when I am alone, I am reminded of the fact that I have no friends. All that I hear are the regrets and the echoes of the empty rooms of my life. How did I get here; it wasn’t easy. Many people are content to live their life alone; I am not one of them.

It’s more than that; I know that it’s about being loved, genuinely loved, loved for who you are. That’s it, it comes down to who you are. Even I want the fairy tale; you know, where two people meet, fall in love and live happily ever after. Does such a thing exist; I’ve so wanted it to; two people, not perfect, just perfect for each other.

Where did this deep anguish of feeling so alone come from; perhaps from a long time ago; this is my story.

Chapter One: Loneliness

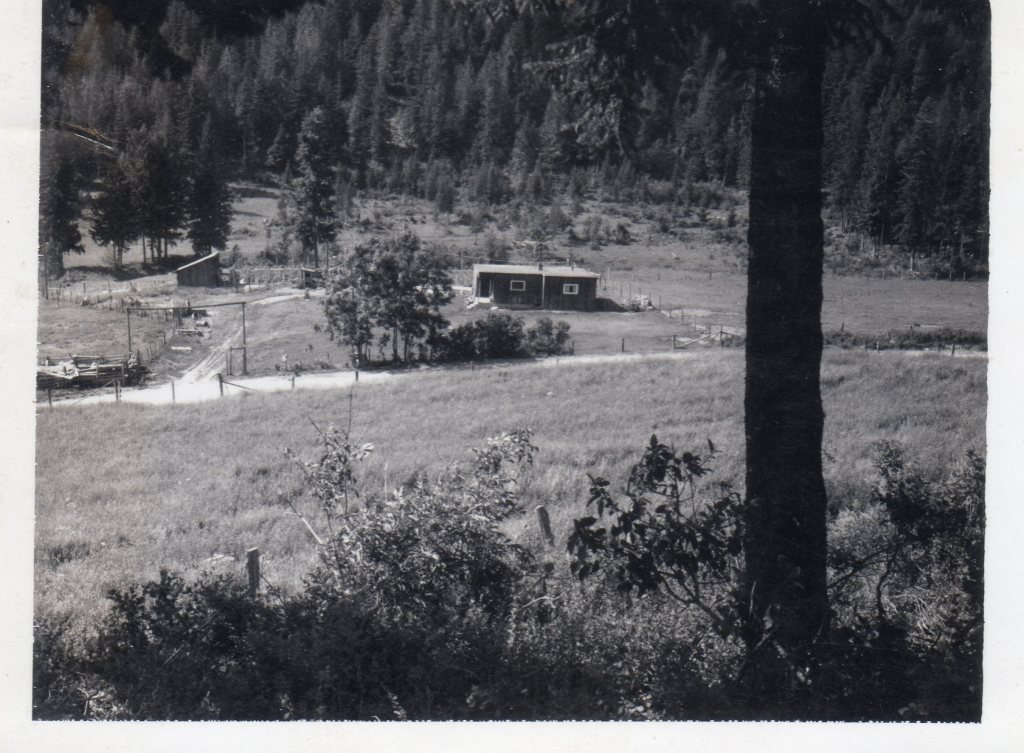

When I was eleven years old my parents sold a business that they owned in Anchorage, Alaska, and purchased a thousand-acre ranch in Eastern Washington. The closest town was a post office and convenience store, a true blink and you miss it roadside spot called Cedonia. My parents’ goal was to have a herd of cattle and horses, mostly horses; a passion of my fathers, something I never understood.

I don’t remember any livestock that first summer, other than our dogs, two Siberian Huskies, Lady and Beauty. They liked the neighbor’s sheep. They liked them too much, and it would someday cost them their lives.

The house was a large affair, bigger than any house I’d ever been in. We had very little furniture, so it was empty, for the most part. I remember the living room being so large and empty that my brother and I could play with a basketball in it without worrying much about damaging anything. Of course, we didn’t do it when Mom and Dad were around, not a good idea. Oh, and I should point out that I had three siblings, as well as my parents and two dogs.

I had one brother, a year younger than myself: a sister, one year older than me, and another sister, three years younger, as is usually the case with siblings. I was much closer to my brother (due to gender), than my two sisters, which I had little tolerance for. For an eleven-year-old, girls were girls, and sibling girls were like a wart in an unpleasant place, always obvious and irritating.

After the trip down the Yukon Highway, about June of that year, it left a short summer that was occupied primarily with exploration. It went by so quickly that I hardly remember any of it. What followed was so traumatic that any fond memories of the summer were lost in the overwhelming events of the fall and winter.

When you’re young you tend not to listen very closely to the day-to-day conversations of your parents. At that time my mind was occupied with how fast I could finish the chores so that I could go hunt squirrels or explore the old, abandoned house on the mountainside, or go dig up newts in the swamp. There were a thousand adventures and a thousand ways to get into trouble; I was determined to find them all. Each day brought something new. I could hardly sleep. The morning sunshine was like the sound of a starters gun in a great race. When you are young and life is full of adventure even the sunshine has a smell. Yes, it smells warm and inviting. Thing is, it’s not just the start of the race, or the day, it also signals that you are running out of time, soon it will be night; the sun is up and you’re running behind. No candy store could compete with what was on that ranch; for a few short weeks it was boy heaven. In my race to discover the new world occasionally something that my parents would say to each other would penetrate my busy mind, and what I heard began to frighten me; everything that was bright and promising was about to turn dark and menacing; my heaven would soon be my hell, and it would change my life forever.

I never knew all the details of what went wrong with the sale of the business, but the bottom line was that the payments stopped, and the problems were such that returning to Alaska was part of the solution. I was too young to understand the legalities of repossession, but not too young to understand what that meant in terms of me. The money from the sale of the business was needed to live on and in turn pay for the ranch. Financial problems created hostilities, and my parents needed little excuse to fight; another reason to find something far away to do.

We lived about nineteen miles from the nearest real town; a place called Hunters. Nineteen miles to a young boy was a major trip. We lived off of the main highway, about six miles via a gravel road. There were a few other homes along the way but the last remaining child living on the mountain had graduated in the spring of that year. Therein lay the compounding problem; district funded bus service. The school district had provided a private bus service down to the highway, all mountain children would then transfer to the regular school bus. The private bussing consisted of the district paying one of the mountain neighbors to transport the children, in their private car, to the highway transfer point. Then the neighbor would pick the children up at the end of the day, at the same place, and take them back home. This is significant for two reasons. First, it was looking more and more like my parents were going back to Alaska to take over the business until they could resell it, probably for the winter. Secondly, if there were no children on the mountain, in the coming school year, the school district would discontinue funding the service, leaving transportation off the mountain, in the future, up to the parents; an expense my parents felt they could not afford.

Finally, the end of the summer came, and with it the decision to return to Alaska. Talk of another decision had also been made. A decision that haunted me day and night sense I first heard the hints of what was to come, my parents did not want to lose the district funding for transportation to the school bus. They were convinced that all the business affairs could be resolved in one winter’s passing, so it was decided that one of us children would stay behind to satisfy the district’s requirements. Everyone knew without saying, who that someone was, but my parents would go through the formality of asking for a volunteer just to make it look like it was my idea. They called all of us children together and explained the situation to us; all eyes turned to me. I knew I was expected to volunteer, and I knew all the reasons why; it wasn’t just that I was the strongest of the kids, no, I knew, I always knew. I knew in the way that I was treated and beaten. I knew because I never heard the words that the others heard. I knew because of the words that I did hear. Like the time my parents didn’t know that I was in the hallway, and I overheard them talking about me. My father said to my mother that I was so ugly. I hated who I was, because I knew that my parents didn’t like me. I remember going off by myself and crying and asking God why I was ugly. I determined then that I couldn’t change the way I looked, but perhaps I could make up for it by being strong, and I was strong, but strong was not enough. Even I knew that. So, I did what was expected of me; I volunteered.

Preparations for the trip were quickly made. Most had already been done, with me in mind as the one who would stay behind. I was not fooled; it was always to be me. The car was packed, even Lady and Beauty would not be left behind.

My grandparents on my mother’s side lived about forty-five miles away. The plan was for them to come for one or two days a week to check up on me; bring groceries and take my laundry, that sort of thing. They couldn’t stay long as they had a herd of cattle that needed to be fed hay twice a day during the winter. They would leave me their dog, Sport, an old Cocker Spaniel- soon my closest companion and my only friend.

There was no TV or radio. There was limited baseboard heating. I could use the kitchen, upstairs bathroom, and mine and my brother’s bedroom. The rest of the house would not be heated, and no rooms would be heated while I was away at school. There was a wood cook stove in the kitchen as well as an electric range. I was to use the wood stove for cooking in order to conserve the cost of electricity; plus, the wood stove produced much needed heat in the wintertime. Like the living room, the kitchen was very large. Every day, when I got home from school, I was to chop firewood and kindling and haul it into the kitchen. I would carry it through the library, then the living room, down the hallway, and then into the kitchen. As I said, the house was very large, and very scary to an eleven-year-old. But I’m getting a little ahead of myself.

The car was heavily loaded for the return trip, as it was for the trip down from Alaska. What few belongings we had brought with us were now going back; the house would be empty of both people and furniture.

I remember that day and the moment of their departure still. After all these years the sight and sound of the overloaded station wagon still echoes in my mind. I hear the gravel popping under the tires as the car slowly pulls away, gaining speed, as I watch it begin to fade in the distance, my brother and sisters waving at me through the rear window, the dogs barking their own goodbyes. I shrank in my mind as I must have in my parents’ rearview mirror. I tried to be brave and strong, but strength was not what I felt. What I remember was a deep penetrating sense of loneliness that filled every part of my being, clear to the depths of my soul. It was a pain that I could not hold within me despite my every effort. I didn’t want to cry, but I did. I cried within my heart. Can a heart cry? Mine did. The voice in my head asked the ever question; why me God? How can I bear this? Finally, the car was out of sight. My Grandparents went into the house to get their things; soon they would be gone too.

I stayed there, rooted to that spot for a long time. I didn’t know what to do with myself. I had never known such loneliness could even exist. I was just a little boy; what do boys know about loneliness? I would learn.

So began the winter of my loneliness.

Today, whenever I am left behind, when visitors or loved ones are driving away, I always stand and wave and put on a smiling face for their departure, feeling that old loneliness tugging at the strings of my heart, threatening the little boy inside, as the tires fade in the distance.

I don’t know, it’s just a thought, but maybe this begins to explain why being alone today is still such a torment.

The Suicide Race

Where did Dad come up with the idea to enter me into the Inchelium suicide race? John Cahill, it had to be him. “Learn everything you can from John Cahill.” my dad would say. John was the oldest cowboy I ever met, he knew everything there was to know about cowboyin. He was as old as the Grand Canyon, with wrinkles on his face just as deep. He wore dirt and dust like some people wear Sunday church clothes. He had a gray ten-gallon cowboy hat that was all sweat stained and horse corral dirty. He always had a brass bracelet that he wore on both wrists, claimed it was an old health remedy for arthritis or some such thing. I think he was part or all Colville Indian. I don’t know where dad met him, maybe at a horse auction. Dad bought Cahill’s entire herd of horses, about forty, including his Appaloosa stallion, Big Smoke. Big Smoke was all white except for big black spots on his rear, classic Appaloosa.

First time I met him was at his place, somewhere near the town of Hunters. He and his wife lived in a dark, hole-in-the-wall, kind of cabin. I remember sitting at the table with dad and Cahill eating a piece of bear jerky that his wife offered me. It came from a bear they killed that winter. It didn’t taste bad, which wouldn’t have mattered because I was raised to eat what was offered no matter what; I was also taught to speak only when spoken to, so I sat, ate, and listened. I remember being really confused at one point about their conversation. I caught bits and pieces as I was looking out the window at the horses in the coral. They were talking about a bunch of hippies marching down some street in Spokane. It made no sense to me; how would a bunch of hippopotamuses be walking down a street in Spokane. (I had no idea what a “hippy” was.) I think I was thirteen then, in the mid-summer of 68′. It would be two more summers before the suicide race. It had to have been Cahill that first mentioned it to dad, and then his crazy idea to enter me and Tink-away, Tink for short.

I love to ride, but not Tink, just about any horse but Tink. She was a bit crazy and unpredictable. Her sire was a Triple A Aqua Champ, her mom was one of the fastest horses out of the gates. Oh sure, she was fast, real fast, but prone to shy (jump sideways), and at the worst time. Take that quarter mile race at the Colville fair, for instance, we were in the middle of the last turn, neck and neck for the lead when she shied suddenly to the right and almost went through the rails on the right side of the track. It was all I could do to stop her in time, and it almost unsaddled me. It was her first race out of the gates, and she was all over inside the shoot. I thought she was going to go over backward while still inside, but they popped the door at just the right time. She came out strong and quickly took the lead. All good till that last turn. I knew I could never trust her after that.

Now dad wants me to take her down the mountain in the Inchelium suicide race? Is he crazy? She’s a dainty, year and a half old pure bred quarter horse, inexperienced and unpredictable, barely more than green-broke. Not to mention that going full speed down a near vertical mountain takes the kind of horse that is big boned, mountain bred, and tough enough to pound rocks underneath any cowboy.

Give me Lightning, fast, strong enough to pull an Angus up hill, and mean enough to literally scream at dad while going down to the ground after dad and three other big men tied up three of his legs in order to throw him. Dad thought that would break his spirit, but all it did was make him hate dad all the more. Lightning, what a horse. He was battle tough, had three different brands, one on the jaw, one on the shoulder, and one on the hip. He had rope burns on all four fetlocks, and whip scars all over his rear. He had been abused by several owners and still stood strong and proud, and he was my horse now. We trusted each other, and together we had never lost a fair fight. Yeah, give me Chief Lightning Foot and we would conquer that mountain and lay it down at the finish line for all to see; and they would cheer in amazement, and awe.

But no, I have to ride that mountain on Tink-away, a mountain that has been known to be the end of many a horse. If a horse loses its footing on the mountain and goes down it will never get back up, and will take down any horse and rider that might be trailing behind it; no time to stop or go around.

There was another big reason that this was a crazy idea. Inchelium lay squarely amid the Colville Indian Reservation, and non-Indians were not always welcome in their events. This was one of those events. I would be about as welcome as Custer was at “The Little Big Horn”. This idea was crazy like its name…suicide.

There was no changing dad’s mind, not that anyone tried, that I know of. I don’t know what mom thought of the whole thing, I doubt she was keen on it. I think it was something that dad would have liked to do himself, but he was too big for any horse going down the mountain. I was the only one who had ever ridden Tink-away, and I was considered the horseman of the family, after dad, of course. This race was like a rite of passage for any horseman. You go down this mountain, and no one can question your skill with a horse. Dad was going down the mountain vicariously through me, it was him that he would see going down the mountain, not me. This race wasn’t about anything other than bragging rights, after all, the winning purse was only worth about three hundred dollars, nothing compared to the value of the horse, not to mention the rider.

Training for the race was no different than training for any race, it was ride every day, and lope for about six miles non-stop. Loping is my favorite stride for a horse; it’s like a smooth rocking chair. The horse has a casual gate, and the saddle never feels more comfortable. Rumor had it that, once upon a time, the suicide race went down the hill across the flats and across the Columbia river. That was before it was dammed, now it’s too wide. Anyway, I don’t know if that was true or not, just what I was told. Tink-away had a bad habit of rearing over backwards when you put the saddle on her or when you first got into the saddle. It was her way of saying, “I don’t like the saddle, and I don’t want you to ride me.”, I think. She didn’t do it every time, but you never knew when she would, so saddling and mounting was always a stressful time. We tried tie-downs, but nothing we tried would break her of that habit. If it happened when I mounted her, I would slip out of the saddle real fast and be standing beside her when she hit the ground, then I would jump into the saddle as she was getting back onto her feet. She would only do it once, and it was always in the beginning. One time my boot got stuck in the stirrup on the right side, the side I would always slip first. I couldn’t get out of the saddle. About fourteen hundred pounds of horse landed on top of me, driving the saddle-horn so hard into my stomach that I swear my backbone could feel it. She got back up and I was still in the saddle, trying to catch my breath. I love riding horses, but that one, I never really liked. The ground was so hard, it was in our driveway. Ouch!

The day of the race was late August of ’70, just before my 15th birthday. It was hot, breathtakingly hot. My shirt was soaked in sweat. I was close to six feet tall but only weighed about 120 pounds. Weight was a big factor in any race. The race would start at the top of the mountain. If you made it to the bottom, then you raced across a long flat field, crossed a paved road, and then sprinted on a dirt road to the finish line at the entrance of the fairground arena. The mountain was made mostly of shale rock, because of that it had been known to cut a horse’s fetlocks to the bone and cripple them for the remainder of their very shortened life. In preparation for the race dad put several layers of medical tape around Tink’s fetlocks to protect them. Fortunately Tink seemed in a good mood and did not rare over backwards when she was saddled, maybe it was just too hot for the effort. The saddle we used was mine, it was light, but strong. The straps were cinched and double checked; it would be disastrous to have the saddle come lose on the hill. Mom had me wear a bright colored shirt so that she could seek me out of the other riders with a pair of binoculars. There is no way to prepare my mind for the race, it was not preparation, it was resignation. I did not want to be there, but I knew all too well not to argue with dad. As much as I didn’t want to be there I still wanted to win. Competition was always about winning. In this case, survival and winning.

To make things worse, Dad was told that no white person was allowed to go down the mountain. The race was sacred to the natives and there would be trouble if I went down. Of course that was like cat nip to dad, no way would he back out. He made a plan. If Tink and I made it down the mountain alright, then we would load Tink into the horse trailer and book out of there before the trouble came. He felt that the threats were credible and he didn’t plan to stick around to find out.

Finally, all the riders mounted their horses and were then led to the top of the mountain by way of a trail that went around the back side of the mountain and to the top. It was a long trek. I was alone with my thoughts and all the knots in my stomach. All the other riders were grown men, all were natives, but not all appeared to be sober. The smell of alcohol was strong. I got the stink-eye look from all the riders, and more than one told me to turn around and go back before something bad happened to me. It didn’t matter that I was a kid, I was not welcome, and they would do whatever it took to make sure that I did not finish the race.

What does one think about at times like this? Did I pray to God for protection, to survive, or to win? I don’t remember. Backing out would not have entered my thoughts, “Sorry guys, changed my mind, have a nice ride.” No, that would not be a thought. This was a bigger deal than my 15-year-old mind would have contemplated. I’m sure that Dad probably came to me early on and explained the race and the possible outcomes, then offered me the right to choose not to enter. I always knew that I really didn’t have a choice. Ride or be thought of as a coward, no, I doubt that I thought about that either. Rite of passage? That’s ridiculous, I was a kid in a crazy man’s sport, if you can call suicide racing a sport. Somewhere along the way every rider had to sign a legal waver agreeing not to hold responsible the organizers of the race in the case of injury or death, yes, death. There is a reason they call it “suicide”. That being said, I never signed such a waver, I was a minor, my parents would have had to sign for me. I was a white kid about to challenge fate with a rock cliff, on a green-broke, dainty quarter horse mare that had less of an idea of what was about to happen that I did. Yeah, I would have thought some about that. I would have been sizing up my competition, looking over every rider and horse, knowing that some had been down this mountain before, or had they? This was a hard looking lot, everyone had their own story, this was a true dirty dozen. I would have thought about dad’s advice, feet forward going down the mountain, lean back in the saddle, give Tink-away her head, and for blankity blanks sake, stay on the blankity blank trail. I had too much to think about on that long, lonely ride to the top of suicide hill, from here on I was on my own. Mom and dad were lined up with everyone else along the side of the road on the home stretch of the race. The stadium had emptied out in order to better see the race and cheer on their favorite horse and rider, undoubtedly, I was not it.

Dad and I had come to the top of the mountain earlier to get a first-hand look at the course. At the very top there was a narrow trail that was the start of the race. It was book ended by two large Pondarosa pine trees and was wide enough for about four or five horses to enter at a time. There were twelve racers, so all the horses couldn’t go through at the same time. If you weren’t in the lead then you either had to hold back and follow, which automatically put you behind or you had to go around the trees. I was told that I had to go between the trees because no one who did not go down the main path had ever made it to the bottom. I had to be in front in order to win. Once we were at the top the starter held a drawing for placement. I was placed on the far left of the field. There was no way Tink could make up the distance to be in the lead, the start of the race was too close to the trail, I could only hope that we weren’t last through the trees. I dismounted and checked my straps and tightened them one last time. I re-mounted Tink. Now we could only wait for the starter to tell us to line up. The horses sensed what was about to happen and they were hard to control. Riders would circle their horses over and over in order to try and calm them, I did the same thing. Some horses would squeal and rare up, bumping other horses in the process. While I circled Tink, I was leaning over her neck, petting and talking calmly to her. She was as nervous as I was. We were ready, the waiting was over.

The sound of the starting pistol was loud and demanding, twelve horses charged for the gap, pounding and shoving for the lead. The rider to my right sliced his whip hard against Tink’s face, forcing her to shy to the left and away from the entrance to the trail. With no time to shift or slow down we flew over the edge of the mountain at full speed, far from the coveted trail. All I could see was empty space in front of me. Tink-away immediately tried to sit back on her haunches but I was determined at that point to go down that mountain as fast as I could make her go. I laid the spurs to her sides and yelled as loud as I could into her ear. To my right two horses and riders went down in a pile of dust amid screams of a pain that was far worse than that of defeat. Everything was happening so fast there was no time to think, only riding, riding for your life and your horse’s life. In a rush of time that could only be measured by one or two breaths of air we found ourselves at the bottom of the mountain. No time to marvel in a feat that had never been done, we were now in an all-out sprint across the valley, there were two horses ahead of us. I yelled again, “Come on Tink, you can do it!” We were closing in as we came to the paved road. Just on the other side of the road we had to take a hard left to sprint for the finish line at the entrance to the arena. I was anxious, victory was within our grasp. I pulled Tink’s head hard to the left in anticipation for the turn. Too soon, we were still on the pavement and Tink’s metal shoes started to slide as she tried to turn before she was across the pavement. Her hindlegs started to go out from under her and it was all we could do to keep from completely going down. We were able to recover but lost too much distance to catch the two leaders. We raced into the arena to the cheers of the crowd, but the cheers were not for us.

No time to mope, we had to skedaddle. I remembered seeing mom and dad standing on the sidelines right where Tink had lost her footing, they saw the whole race, and my mistake at the end. Tink and I quickly got to the horse trailer where mom and dad were waiting. A quick examination of Tink’s fetlocks revealed that all of the protective tape, along with hair, and some hide had been scraped off on the way down the mountain, the skin was raw but the tape had done its job and she would be fine. We loaded Tink into the trailer and headed for the fairy crossing and the safety of home turf, on the other side of Lake Rosevelt.

I don’t remember much being said to me about the race, but I always had a sense that mom and dad were more than a little proud of me. As for me, I’m still disappointed about not winning, but we made a good showing and we survived the mountain, off the trail. That’s a race I will never forget.

Sad to say, two riders were taken to a local hospital, and two horses had to be put down. Sometime after they discontinued the suicide race due to the danger and the property owners liability concerns.

‘

*”Riding horses was another favorite pastime. There were always several horses available, since most people owned them for personal transportation. We were used to riding bareback as boys, and the better riders usually ended up racing one another before the day ended. When these riders matured they competed in races across the Columbia River and back. This was a dangerous contest, and both horse and rider had to be strong to survive the rigorous race. The best riders traveled to distant towns and competed for cash prizes in rodeos.” Page 65, second paragraph of the, ”White Grizzly Bear’s Legacy:Learning To Be Indian” By: Lawney L. Reyes, a personal biography. (Copyright 2002)

The Train Holdup

I would like to share a short story, largely summing up my connection to trains.

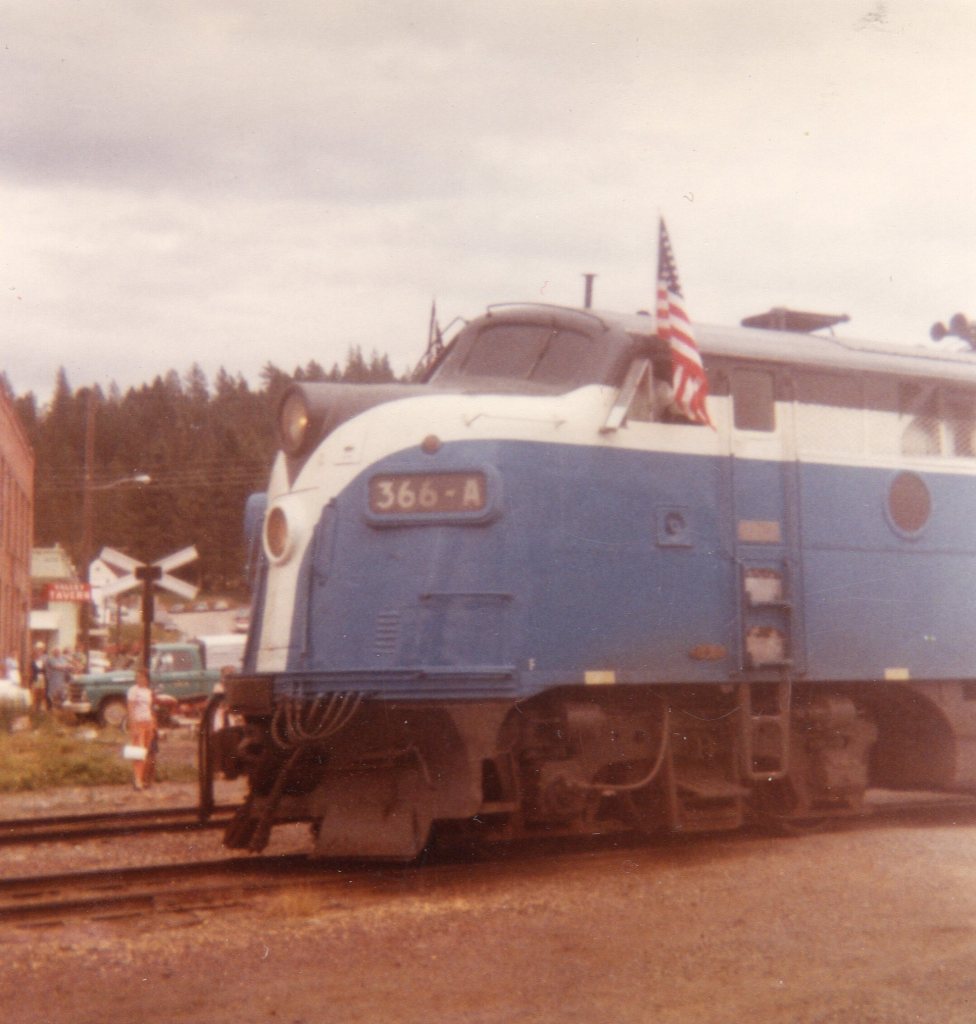

It was late June of 1969; I was 15 years old. At the time my family lived on a small horse ranch near a small town in eastern Washington named Valley. My father heard of a special Great Northern train that was coming from Spokane, Washington and ending in Chewelah, with several stops along the way, including one at Valley. The reason for the event escapes me.

My father, being a big prankster, recognized a sure opportunity. He managed to find out the general time the train would be stopping in Valley, that it would be picking up passengers, mostly children, some dignitaries, and clowns to entertain the children. My father, and a friend, whom I only knew as “Bob”, determined to stage a train holdup, my brother and I were to take part, a sort of introduction to manhood.

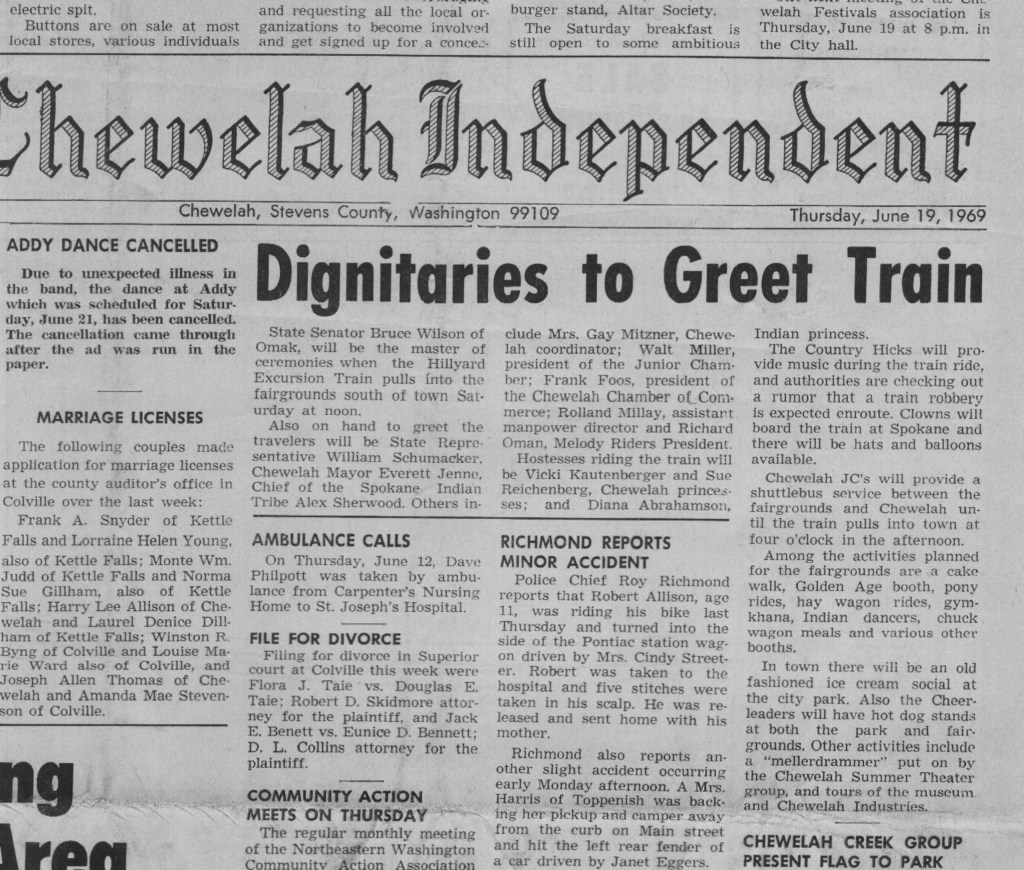

Word of the holdup managed to get out prior to the event. The local paper, The Chewelah Independent, reported in an article on the front page of the June 19 issue, just days prior the holdup, “authorities are checking out a rumor that a train robbery is expected enroute.”

On the morning of the event, we hauled the horses to town by truck. Not knowing exactly when the train would arrive, we were exceedingly early. The skies were slightly overcast, and it was a bit chilly. We were dressed in our standard western regalia, cowboy hats and boots, blue jeans, chaps, and a neckerchief to pull up to cover our faces during the dastardly deed. Dad and his friend Bob had real guns with live ammo.

No gang of outlaws worth their salt would be complete without a bottle of whiskey to warm the bones and calm the spirits. Dad thought of everything. As mom would say,” A swig of that will cure what ails ya.” So, the bottle was passed around. Once was enough for me; my throat burned, my eyes watered, and being a man never seemed so unappealing, but I kept up the blustering front, fooling no one, I’m sure.

My brother always had an inordinate attraction to bees. That is, they were attracted to him. While we were waiting for the train to arrive, standing with the horses, he managed to step in the middle of a wasp nest. He had a few more reasons to remember that day than I did.

The holdup was to take place in the heart of town and a large crowd had gathered for the arrival of the train. I doubt many knew of my fathers’ plans. After a two hour wait, about noon, the train came rumbling into town. The moment had arrived.

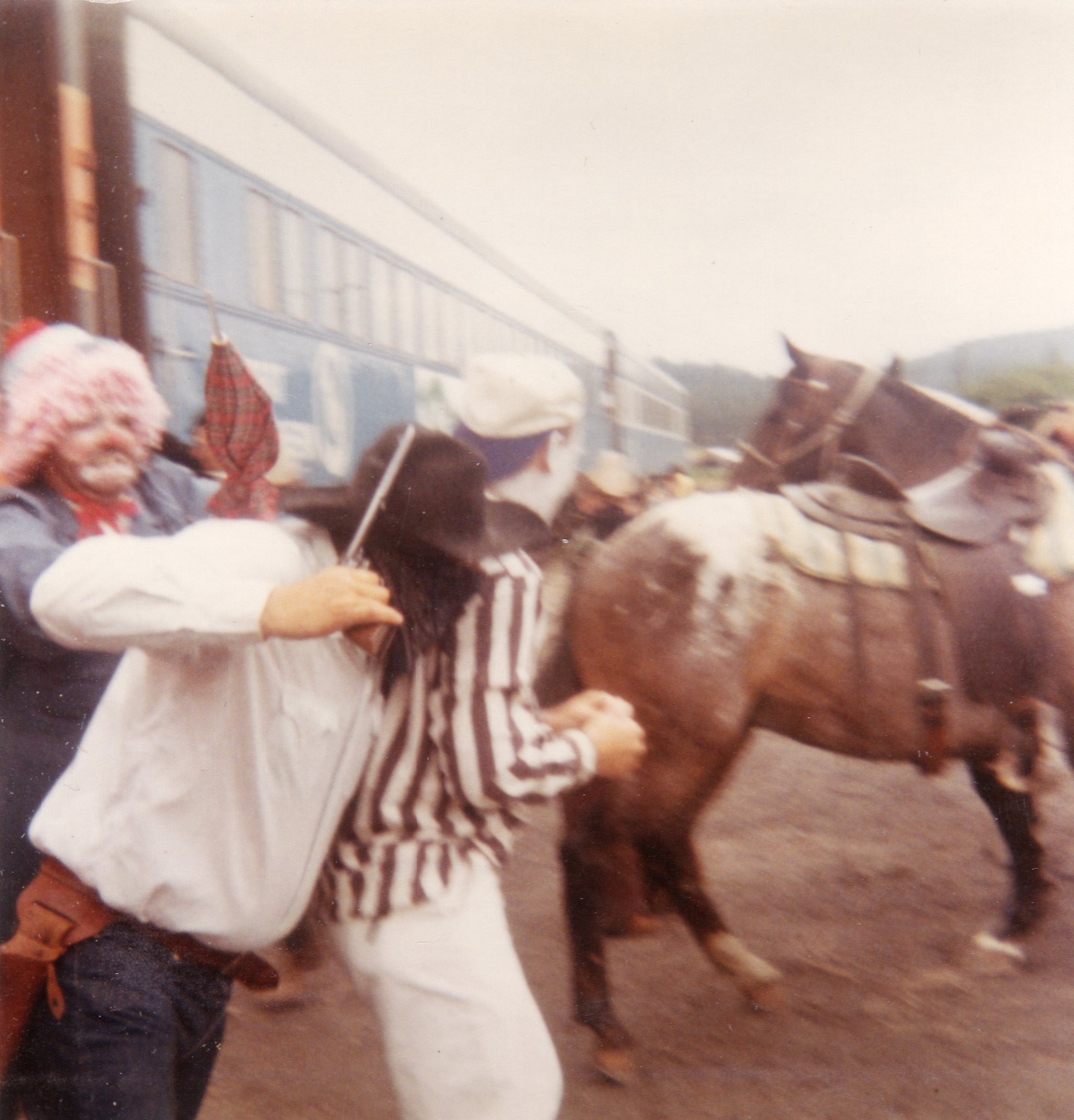

We mounted our horses, raised our masks, and charged after the train. Shots were fired in the air as the engine came to a halt. Dad and Bob leapt off of their horses, threw the rains to my brother and I and boarded the train. The dust, noise, and crowd spooked the horses so much that they were hard to hold. Next thing I knew Dad came off the train with one arm wrapped around a clown and one arm waving a gun in the air; more shots were fired. Another clown came up behind Dad and began hitting him with an umbrella. Dad mounted his horse, pulled the first clown over the saddle in front of him and off we all went, guns a blazing.

We let the clown go about seventy-five yards later. Thus ended my first experience with trains. Horses, trains, guns, and clowns…what a day to remember.

Gowning up in the 60s

I was seven years old in November of 1963, second grade, when the news came across our black and white, very modern television set, President John F. Kennedy has been assassinated. It was Friday, just after noon, six days before Thanksgiving. We were let out of school early because of the assassination. Due to the difference in Alaska time the official announcement of the president’s death came just before noon. The whole nation, including our family, were glued to their television sets and radios, waiting for any news of the president’s well-being, praying for the best. When the news finally came, mom sobbed. I’d never seen mom cry before that day. At my age, I didn’t know much, but that day I knew that our president had enemies, and because my mom cried for him, I also knew that he was loved by many. How does a nation celebrate Thanksgiving under those circumstances? The assassination was followed by accusations, conspiracies, the assassination of the alleged assassin, more conspiracies, investigations, and then the nation was left in the dark; the books were closed. The government declared the case closed, they had gotten their man, Lee Harvey Oswald, and he was dead, killed before he could answer any questions.

No one believed them, no one at all. If it wasn’t Oswald, then who really fired the shot that killed the president of the United States of America? People want to know the truth, and they will never stop asking, “Did our own government kill the president?” The truth would be hidden for decades, maybe forever.

It Didn’t End There

The Swinging Sixties, a decade that will never be forgotten. It was both my youth and my emergence into adulthood. I was surrounded by iconic moments, both personal and external. It was ten years of constant defining moments for me and my siblings.

Good Friday

What does Good Friday mean to you? To many it marks the day Jesus was crucified, followed by three days and then his resurrection, Easter Sunday. Odd, a day that represents the crucifixion, the suffering, and the death of Jesus, the son of God, is called “Good”. The goodness obviously comes from his resurrection three days later, but really, I think that the day could be called many other things besides “good”.

For Jews this day marks the Passover, the day of freedom from Egypt. In short, Good Friday is a holy day for many millions around the world.

Good Friday is sometimes referred to as Black Friday, a name I could more relate to when at the age of nine years old.

Good Friday, March 27, 1964 started out as a great day, after all, it was the last day of the school week. There were several other reasons to feel good about this day, it was sunny, but cold, after all, Anchorage, Alaska is still cold in March, with plenty of snow still on the ground. Easter Sunday was three days away. Life was good on Good Friday, and then it wasn’t. At 5:36 P.M. I was just arriving at the back door of our home, after visiting with friends in our neighborhood. I was just reaching for the door when the ground began to shake, it was like huge waves of shaking. I tried to stay on my feet but soon realized that I couldn’t, so I just sat down on the ground right where I was standing. The shaking seemed to go on for ever ( I would later learn that it went on for over four minutes.) I had never experienced an earthquake before, and didn’t realize at that moment that that is what was happening. While sitting on the ground I began to wonder what was causing the ground to shake so terribly. My mind raced for some explanation. My brother and I slept in the basement, near a large furnace, we often imagined our fate should it ever blow up. Is that what had happened, did the furnace blow up? Mom and Dad were at work, but my brother and two sisters were in the house. I became frantic in my imagination, were they alright? The ground had not stop shaking when I jumped up and through open the door. I was nearly knocked over by our three dogs bursting out the door, Lady, Beauty, and Vicky, two Siberian huskies and a Doberman Pincher. they had been shut inside the mud room. The mud room was located at the top of the stares that led down to the basement, while another door led into the house. I couldn’t see anything looking down into the basement but darkness. After the stampeding dogs got past me, and with the shaking nearly stopped, I reached the door leading into the house proper. I through open that door and yelled, “Is everyone OK?” No answer came back to me, just silence, and a scene that I would never forget. Behind that first door was the kitchen, what was left of it. There was broken glass everywhere. Everything that was in a cupboard was now on the floor. I continued through the kitchen and into the living room, still hollering for my siblings. Like the kitchen the living room was a shambles, even the T.V. , with an open, built in stereo had fallen onto it’s face, nothing was upright. All that could be seen in a flash, but still no answer from my brother and sisters. The front door to the house was located on the far end of the living room. The door was flung wide open. I made my way through the ruble and out the door where I found my sisters and brother standing in the snow. Out of fear they had fled the house so rapidly that they didn’t have time to put on shoes, and were now huddled together, crying hysterically, not knowing what was happening or what to do, too afraid to return into the house. Thankfully, no one was hurt.

It is strange what children think when faced with a disaster that they don’t understand and can’t begin to . To us all we could see was our home. We had no idea that we had just experienced the largest earthquake recorded in history, nor the extent of the damage caused through out the state and beyond. To us it was just our home. Moments after I joined my siblings a neighbor came running across the street. Out of breath, the man ask if we were alright, we assured him that we were, but now we had a much larger concern. In unison we told him that we were going to be in so much trouble from mom and dad when they get home and see what a mess the house is. We did not believe him when he said that they would understand and not be upset. As we turned to go back into the house, the sky had clouded up and a lite snow began to fall.

That was the beginning of Good Friday, 1964, and there would be no Easter Sunday for us or for anyone in the State of Alaska this year.

The Aftershock

It is important to note the sheer power of this earthquake. It was measured at 9.2-9.3 megathrust, equivalent to “400 times the total [energy] of all nuclear bombs ever exploded” until that time. It raised the land over 30 feet in some places. In addition it was followed by over 560 aftershocks and a tsunami wave run-up that was as high as 170 feet. The primary quake lasted for an astonishing four minutes and 38 seconds.

Meanwhile

While I and my siblings were experiencing the quake so were our parents. Mom worked in some capacity for the State of Alaska. She was a secretary, that was all that I knew about her job. Dad owned his own car shop, where he repaired cars and also built cars that he and mom raced on the Alaskan circuit. Mom had gotten off work at 5 p.m., and had stopped at the shop to visit Dad on the way home. The shop was only a few blocks from where we lived. At the time of the quake Dad had a car on a hoist about seven feet in the air while working underneath it. Mom was standing under the car talking to him when the car started rocking back and forth. Mom attempted to get out from underneath the car but was knocked in the head by the swaying car, knocking her to the ground back under the car. She got up only to meet the same fate. On the third attempt she was able to escape the swaying car with Dad and they got out of the garage. Strangely the car never fell off the hoist.

My memory is completely lost as to mom and dad’s arrival home, despite that lack of recollection I am certain that we were not in trouble over the state of the house, which must have been a great relief. I would have remembered if it were otherwise.

Other than the house being a complete mess, it was relatively undamaged, shaken but not broken. Many homes were uninhabitable, but somehow most of our neighborhood was unscathed. Still there was no water or electricity, so we were packed up and hauled to some friends of mom and dad’s, where we all stayed for a few days. To us kids it was now just one big adventure, a long sleep-over. They had children our age, so life was great. During the day we, (kids) would all walk around the neighborhood and look at all the damaged homes. We had no sense of how devastating the situation was because we were relatively untouched by the gravity of the disaster. Many lives were lost and the city was all but destroyed, with some downtown buildings completely swallowed by the shifting, and raising and falling of the ground, words and pictures can’t really describe how bad the destruction was.

What You Don’t Know

At nine years old I understood, kind of, what I was told about the earthquake, yet I didn’t really see what I was told, so I don’t think I really knew what had happened. I didn’t see death, and I didn’t see much of the destruction. I recall that when I first felt the swaying of the quake it reminded me of one of those nickle, (now fifty cent), rocking horses that you find in front of grocery stores, a fun ride, so I sat down and enjoyed it, until my little brain began to wonder what really was happening. I wasn’t in the house, so I didn’t share with my siblings the fear of seeing everything falling at the same time as the feeling of the ground moving, that which caused them to flee the house in terror. I never felt that, ever. That being said, the fact is, I was in the middle of the second worst earthquake ever recorded in the history of the world.